Migration is one of the major forces shaping the world today, with more than 60 million displaced people.

“Never in history have we seen this many simultaneous displacements across the globe and these people are not going home any time soon,” says Mostafa Minawi, assistant professor of history and Himan Brown Sesquicentennial Faculty Fellow. “This is a global population redistribution and it will hit us whether we like it or not.”

Although migration has always been a factor in world history, war, civil unrest, economic dislocation, and climate change are combining to create what some policymakers call “disposable” populations. “It’s in our interest to study migration, to ask, what are the policies that are uprooting populations?” says Maria Cristina Garcia, Howard A. Newman Professor of American Studies. “What are the consequences for those who are uprooted as well as for the host societies who are then going to have to accommodate them?”

Syrians refugees are currently attracting a great deal of attention, as a visible by-product of regional power struggles and a reminder to Americans of the threat ISIL terrorism poses, but Garcia emphasizes the importance of remembering that there are also migrant crises in Eritrea, Burundi, Libya and elsewhere.

Forced migration issues are the most urgent to address, and the most difficult, given the inconsistencies, inefficiencies, and inadequacies of global refugee and immigration policies. From 2010-2013, the Institute for Social Sciences conducted a collaborative project examining Immigration: Settlement, Integration and Membership. Participants included political scientists Michael Jones-Correa and Mary Katzenstein and anthropologist Vilma Santiago-Irizarry, as well as historians Richard Bensel, Derek Chang, and Garcia. The group examined labor markets, formation of policy, new gateway cities, and demographic shifts across the country.

“Students enroll in immigration courses because they are troubled by what they read in the news. They want to understand who’s migrating to the US, and what the appropriate response should be to that migration," says Garcia. "They think the anti-immigrant discourses are unique to their day. But when they study history, when they examine migration and policy over a longer period of time, they see patterns emerge. History, and the humanities in general, remind us to look for those patterns, to look for the similarities and the disjunctures, to see what conclusions we might reach.”

“Quantitative science looks at large numbers of people, what factors push lots of people to places and what factors pull them to a place," says Leslie Adelson, Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of German Studies. "For example, Germany now has big pull factors and Syria has big push factors. What humanists bring are the heightened attention to blind spots in categories we use in analysis and a heightened attention to how perceptions are formed and how they can be changed in productive and creative ways. Not just creating empathy for migrants, but acknowledging existing bonds for and among migrants, and forging new bonds.”

Why leave home?

Why do people leave their homes? For some it is an economic decision; for others, a reflection of their politics. For an increasing number of displaced persons, the reasons are safety, either from war and violence or from environmental dangers.

But whether someone is an economic migrant who chooses to leave his or her home in search of better economic opportunities or a refugee fleeing war and persecution is not always a clear distinction. The Haitians who left their country in the 1970s and 1980s, for example, were assumed to be fleeing their island because of poverty, since Haiti was one of the poorest countries in the Americas. “But Haiti also had despotic leaders,” points out Garcia. “It was a combination of political and economic factors that drove people to leave. Categorizing migrants as either economic migrants or political refugees doesn’t get at the heart of their experience.”

Blake Michael ’16, a government major and College Scholar studying immigration and migration, notes that the gray area surrounding “economic migrants” means that although they’re often fleeing harsh conditions which would engender sympathy, their reception upon arrival in their new country is often very different from that received by those categorized as forced migrants.

Climate refugees

Populations displaced by weather patterns are nothing new; famine because of drought or flooding is an ancient story. Those displaced by such weather-related patterns have traditionally been seen as economic migrants. But the global climate change now facing humanity has spawned a new term, that of “climate refugee.”

“Climate is a threat multiplier,” Garcia says. “Much of the political upheaval of the last 40 years has had an environmental component. Environmental disasters displace people internally, or force them to cross borders, and these uprooted populations then exacerbate problems that may lead to civil unrest or political conflict. Natural disasters have cascading consequences.”

Adds Michael, “As sea levels rise and weather becomes increasingly destructive, it is highly likely that the millions of people living in low-lying areas across the world (particularly in South-east Asia) will find it incredibly difficult if not impossible to continue to survive in the manner in which they have lived for thousands of years. This will necessitate a massive migration, which will in turn create a major humanitarian crisis which it is doubtful the world is prepared to address.”

Although the international community is already grappling with questions of culpability and responsibility for climate change degradations, the current international legal definition of refugees does not include climate refugees. Some international treaties have recognized the issue; at COP21, for example, there was a recognition that climate change contributes to allegedly disposable populations.

Garcia, who is currently working on a book about the environmental origins of refugee migrations, emphasizes the urgency of figuring out how to respond to populations most at risk as a result of climate change. Environmental disasters are not a new phenomenon, of course, but the number and scale of such disasters seems to be escalating.

“If disaster hits one part of the world, it hits the rest of us,” adds Adelson. “We need sustainability in every arena in order for livable futures to be had.”

Migrants in America

To call someone a “refugee” doesn’t mean that person will be allowed to settle in the US or elsewhere: the term has a specific legal meaning. To qualify as a refugee under U.S. law, refugees must have crossed an international border and be outside their country of origin. They must provide proof of past persecution and have a reasonable fear of future persecution, as well as failure to receive protection from the state. They must not have inflicted harm on others (soldiers, including child soldiers, are therefore not eligible).

Each year the US establishes a numerical ceiling for refugee admissions, with sub-quotas for different regions of the world chosen according to State Department priorities. Over the last thirty-plus years most of that refugee quota has gone unfilled. Since the attacks of 9/11, says Garcia, American refugee policy has been driven by the fear of sponsoring would-be terrorists.

But government policies are only one of the driving forces behind population displacement. Business policy, too, can have significant impact – such as a company that strategically shuts a factory in the U.S. to move it just across the border to Mexico in order to pay lower wages and taxes and not deal with U.S. labor unions or strict environmental laws. The new factory motivates job-seekers to come from all over Mexico; if they can’t find work in the new American company, the next logical step is to cross the border into the U.S.

“When I tell my students that the U.S. contributes in many ways to dislocation and migration, the students don’t really get it until they read particular business case studies,” says Garcia.

Displacement in North America

One displaced ‘nation’ remains mostly invisible to Americans, says Jolene Rickard, associate professor of history of art and director of the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program: the Haudenosaunee or Six Nations, (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora) straddle the border between the U.S. and Canada, near Massena, New York.

As Rickard explains, the Akwesasne Mohawk community is situated on both sides of the border, so on a daily basis their population must engage with Homeland Security and border controls, experiencing treatment like migrants on their own territory.

To address this irony, in May 2016, Rickard convened a conference to examine the strength of the Jay Treaty in relationship to the movement of Haudenosaunee people in their own territories at the U.S and Canadian border (the 1795 Jay Treaty and its subsequent codifications guarantee “Native Indians born in Canada” the right to enter the United States for the purpose of employment, study, retirement, investing, and/or immigration).

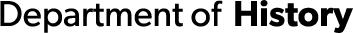

Rickard’s research involves calling attention to the displacement of Indigenous peoples in the U.S., in particular the impact of the Clinton-Sullivan Campaign of 1779 against the Cayuga and Seneca Nations by marking the resettlement of the Cayuga peoples in their homelands with place based installations.

Jolene Rickard, "Fight for the Line," 2012

Migration Myths

What people believe, the stories they tell one another about displaced people – and the stories politicians tell – have a powerful effect on how immigrants are treated. These stories change over time, though, and in response to changing situations. How will the current refugee crisis remake the story of migration?

“The humanities are very good at helping us understand more effectively how over time the story of migration that gets told takes on new nuances and functions and sometimes entirely different shapes,” says Adelson.

In her book, “The Turkish Turn in Contemporary German Literature: Toward a New Critical Grammar of Migration,” Adelson examined the effects of Turkish labor migration on German literature and how its depiction changed over time. Turkish laborers who came to Germany in the 1960’s as part of an agreement between the countries were depicted as taking advantage of a labor opportunity for an international working class. In the 1980’s and 90’s this history was transformed into a story of ethnicity and ethnic conflict. After 9/11, themes of religious difference began to overlay this narrative, as part of the increasing focus on religious and secular conflicts.

In addition to Adelson’s current class in German, “Changing Worlds, Migration, Minorities and German Literature Since 1945,” she will co-teach a University Course in Spring 2017 with Sabine Haenni, associate professor of Performing and Media Arts and director of the American Studies Program, on the subject of migration. Taught in English for a broader audience, “Imagining Migration in Film and Literature” will focus on asking what role the imaginative arts can or should play in public perceptions of migration.

“Humanities and particularly arts within the humanities are especially good at helping us understand how we form perceptions of ourselves and those we deem to be other than ourselves; the social fabric that binds us and that which tears us apart,” says Adelson.

One of Garcia’s current projects is a book tentatively titled “American Origin Stories,” which looks at the stories we tell about ourselves as a nation as an immigrant people and examines which stories have a basis in fact and which are constructed over time for particular purposes. She also teaches a course on the topic, US Immigration Narratives.

Opportunities for Student Engagement

Bodies at the Borders, a distance learning class taught by Debra Castillo, professor of comparative literature, and Anindita Banerjee, associate professor of comparative literature, gives Cornell students the chance to directly engage with students in the border cities of El Paso, Texas, and Calcutta, India. As Margaret Gichane '12 recalls, the class "added a lot of context that you can't just look up. Hearing people on the ground experiencing these things day-to-day adds a different perspective from what we read in the text."

Some of the issues raised in the class were explored more deeply in a conference Castillo and Banerjee organized at Cornell, “Guatemala/Gujarat: Marketing Care and Speculating Life” on May 6-7, which focused a comparative lens on Gujarat, birthplace of India’s booming child surrogacy economy, and Guatemala, a major source for international adoptions.

Garcia also teaches a service learning course using Ithaca and Tompkins County as its study focus. Students working with different agencies have opportunities for interaction with Burmese, Tibetan, Ukrainian, Guatamelan, and many other immigrant communities in the Ithaca area. “They get to see how immigration plays out in their backyard,” says Garcia.

With a grant from Engaged Cornell, the Latina/o Studies Program will offer additional opportunities for students to engage with the Latina/o community in Ithaca, such as Castillo’s Cultures and Communities service-learning course. Students will engage in targeted research and arts work with Latino/a culture-related organizations in Tompkins County like Cultura!, No más lágrimas, and the Latino Civic Association.

Beyond Survival

A three day conference at Cornell last November, Beyond Survival: Livelihood Strategies for Refugees in the Middle East, engaged academics and practitioners in a multi-disciplinary exploration of strategies to improve short and long term livelihood opportunities for refugees in the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin. Discussions focused on evidence-based interventions for overcoming legal barriers and policy impediments to refugees' access to education, health care and work. The conference also addressed the role that universities can play to help improve the lives of refugees and asylum seekers at a time of surging global population displacement crises.

“The main question was what can be done and how can Cornell as a university be a leader -- and what does it mean to be that leader?” explains Minawi, director of the Ottoman Turkish Initiative, which co-sponsored the conference, along with the Clarke Initiative for Law and Development in the Middle East and North Africa, Cornell University Law School, Weill Cornell Global Emergency Medicine Division. “We talk about bringing Cornell to the world and the world to Cornell, so how can we be leaders in acknowledging our responsibility in a global environment?”

Minawi is exploring ways that Cornell can be involved in helping provide higher education access to Syrian refugees, such as partnering with universities in the U.S. or in host countries, providing scholarships, etc. “We’re an institution that thinks at a global level and this is an opportunity for us to take the leap into international affairs through what we do best: education,” says Minawi.

Because education in Syria was free, many of the Syrian refugees trapped in camps for years are highly educated, explains Minawi. Aid organizations strive to provide basic education for young children, as well as food and shelter, but this means that tens of thousands of Syrians are losing out on the chance for higher education.

“When people go to university they better not just their own lives but also the lives of their families and community,” says Minawi. “When access to higher education for a family is interrupted, the impact will be felt for generations to come.”

Big Ideas Panel

On April 12, the College of Arts and Sciences brought together faculty working on aspects of migration in a Big Ideas panel, part of the New Century for the Humanities celebration. The event was held in the Groos Family Atrium in Klarman Hall and featured Garcia, Iftikhar Dadi MA ’01, PhD ’03, associate professor of history of art, and Alejandro Madrid, associate professor of music.

Dadi’s talk explored his latest book, on Anwar Jalal Shemza, an immigrant to Britain from its former colonial territory that became Pakistan. Dadi traced the impact of Shemza’s migration on his work and his identity, including an existential crisis when he destroyed all his artwork, writing, “The search was for my own identity. Who was I?…I had lost my home. I was an exile, homeless, without a name.”

Shemza settled permanently in England in 1961 after an unsuccessful attempt to find work in his home city of Lahore. Dadi writes that Shemza’s “diasporic existence was now an immanent, indefinite and unending condition” that deeply affected his art. One example of the anguish of this diaspora were the later paintings that he made deliberately small so he could travel with them: even in their form, says Dadi, is a sense of displacement.

In his talk, “The Intersection of Migration, Sound, and Music in 21st-Century U.S.,” Madrid addressed the migration anxieties being expressed in contemporary political rhetoric, and how sound and music may intersect these issues. Trump’s characterization of Mexican immigrants as rapists and drug dealers, said Madrid, “are a political response to what we now understand are the main anxieties that fuel his campaign, a widespread idea among a white sector of the electorate that immigration is changing the United States, making them lose the invisible upper hand that their race-based privilege had bestowed on them for generations.”

Madrid stated that songs like Emilio Estefán’s “We are all Mexican” and a variety of sound-based memes show music and sound as important components in the responses to Trump’s remarks. Madrid also suggested that “music and sound became central in a struggle against the symbolic invasion of the media and blogosphere represented by Trump’s so-called revolution. Music’s fluidity allows it to cross borders without the required paperwork…[allowing] migrants to …. penetrate the safe limits that whiteness builds for itself in the virtual world of social networking.”

Garcia in her talk pointed out that the number of displaced persons in the world requires an emphasis on burden sharing and multilateral responses. “We can’t work unilaterally to address disposable populations in the world,” she said. “The policies of one country will affect others, as we see happening in Europe today, and as we saw in the Central American refugee crisis of the 1980’s, when Mexico’s immigration policy had consequences for the U.S. and U.S. immigration policy had consequences for Canada.

“Americans can’t ignore these challenges and hope problems will go away. We are part of the international community. The sciences can solve problems and potentially improve the quality of life for all, but the humanities and social sciences help us understand the human experience,” said Garcia.

This feature is part of the New Century for the Humanities "Big Ideas" project to explore broad contemporary themes in the humanities. The New Century for the Humanities is a series of events and projects initiated to celebrate the opening of Klarman Hall, the first building dedicated to the humanities on Cornell's central campus in more than 100 years.