June 2016 update:

Chuck F. Feeney ‘56 (left) with Christopher G. Oechsli, President and CEO, Atlantic Philanthropies.

The Atlantic Philanthropies, created by Charles F. Feeney ’56, made its very first grant in 1982 to Cornell University. By the end of this year, the foundation will conclude its grant-making, realizing the full impact of the foundation’s largesse within its founder’s lifetime and fulfilling Feeney’s commitment to “Giving While Living".

Among Atlantic’s end-stage grants is a $10 million grant to the Center for the Study of Inequality (CSI), one of the largest ever for the social sciences at Cornell. Funding from Atlantic in the late 1990s helped to create CSI as the university’s hub for the interdisciplinary study of inequality. The new grant will endow the center’s directorship, expand its staff, and stimulate research, outreach and policy impact through faculty fellowships, a seed grant program, conferences and a visiting speaker series.

"The College of Arts & Sciences looks forward to working with The Atlantic Philanthropies – and with other institutions in its network of partners – to address inequality in all its forms,” said Gretchen Ritter ’83, the Harold Tanner Dean of the College of Arts & Sciences. "

Under Kim Weeden’s leadership of the Center for the Study of Inequality, we are poised to become a world-class research leader, as well as a major resource for developing more effective policy solutions to one of the most significant threats to democracy and social inclusion in our lifetime."

Inequality is one of the central challenges of our time, and with historic increases in income and wealth inequality in recent years, public and scholarly interest in the topic has skyrocketed. The College of Arts & Sciences is a leading center of scholarship on inequality, drawing strength from its many departments and collaborations across the university.

Inequality in the United States takes numerous forms, says Richard Miller, director of the Program on Ethics and Public Life (EPL): unequal political influence, unequal opportunity, the concentration of income and wealth at the top, the persistence of stark racial inequalities and inequalities in education. These factors reinforce each other, challenging those who seek policies that help meet currently unmet needs and reduce burdens of poverty.

“The social scientific approach to studying inequality dovetails really nicely with the humanities,” says Kim Weeden, director of the Center for the Study of Inequality (CSI), Jan Rock Zubrow '77 Professor in the Social Sciences, and chair of sociology. “Understanding the sources of inequality, how it affects different groups of people, our political institutions, our economy, is very much in line with Cornell’s value of doing research that matters. It ties in with the public engagement mission.”

Adds Weeden, “all human societies have been characterized by some sort of inequality. Even many hunter gatherers had nearly complete gender segregation and resource scarcity. Inequality has always been with us, as much a part of the human experience as love and death.”

Asking Why

Moral questions of what should be done about inequality are those that humanists are well equipped to illuminate, such as the moral importance of reducing inequality of political influence and the extent to which the best-off should be taxed to help others, says Miller, the Wyn and William Y. Hutchinson Professor in Philosophy

The facts have people alarmed, says Miller, such as the stagnation of median income and the dramatic increase in CEO salaries (from 30 times the wages of the average worker in the mid-1980’s to 300 times now).

“But why are these inequalities important? Reflection on why we should care helps people reach across political divides in discussing what should be done. We have a moral responsibility to seek shared moral convictions that yield yardsticks for judging proposals for change,” says Miller.

This semester the Ethics and Public Life program brought six leading inequality scholars to Cornell for the “Inequalities: How Deep? Why? What Should Be Done?” lecture series. Based in the Philosophy Department, EPL promotes interdisciplinary learning about morally central questions concerning public policies and social, political, and economic processes. As part of this interdisciplinarity, Miller worked with sociologists, political scientists and economists throughout Cornell in planning the series; he notes the special help of CSI in the series’ success. Faculty and graduate students from eleven departments took part in workshops and informal discussions with the speakers. The public lectures were attended by large audiences, sometimes over two hundred, and were discussed in a new set of small-group discussion courses, “Discussions of Justice.”

“Our work in EPL is a good example of how the humanities can provide context and depth for broader conversations,” says Miller. He is currently at work on a series of essays that will form a book, “Ethics of Social Democracy.”

“Some philosophers think government should meet a broad array of needs that include but go way beyond helping poor people,” says Miller. “What are the moral principles we can appeal to in order to justify use of a state which doesn’t’ always benefit everyone? But if you base beliefs on moral principles alone you are a fanatic. And while politics is about forcing people to do things, there should always be a moral basis for that forcing.”

Crime, Poverty, and the Criminal Justice System

Under Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society in the 1960’s, the root causes of crime and poverty were seen as embedded in legacies of racial oppression and “blocked opportunities,” says Julilly Kohler-Hausmann, assistant professor of history. But in the 1970’s the notion that crime and poverty are the result of deviant, maladjusted individuals or a cultural pathology became ascendant. Punishment was the logical response to such a belief.

Kohler-Hausmann is a member of an interdisciplinary team at the Institute for Social Sciences working on the collaborative project, “The Causes, Consequence and Future of Mass Incarceration in the United States,” led by Peter Enns, associate professor of government. The team, which includes members from the College of Arts & Sciences and College of Human Ecology, is examining the factors leading to mass incarceration and the circumstances that shape the risk, severity and duration of one’s contact with the criminal justice system. The goal is to help inform the policy debate about whether and how to reform the U.S. criminal justice system.

The decline of the welfare state and its social programs and the rise of mass incarceration were connected, says Kohler-Hausmann. Research shows that there’s an inverse relationship between the amount of money spent on social welfare and that spent on the penal system.

In the U.S. the expansion of the penal system saw a dramatic retrenchment of particular social programs; while social insurance programs persisted throughout the last half century, programs targeting marginalized populations declined precipitously. The value of cash support to poor parents through Aid to Families with Dependent Children(AFDC) fell by half between the 1970s and 1990s, where Social Security benefits were indexed to inflation and maintained their value. Populations and communities most dramatically affected by the expansion of the penal system have also seen dramatic reductions in state support.

Kohler-Hausmann is examining the historical processes that produced these changes. “I view it as the result of broad-based struggles over the causes of social inequality,” she says. “During the 1970s, debates escalated over the causes of social marginality and the state’s capacity -- or responsibility -- to resolve them. My book is chronicling the ways that enacting punitive drug, crime, and welfare policy helped produce answers to these questions—answers that explained disorder and inequality as the work of incorrigible, racialized deviants, such as 'drug pushers,' 'welfare queens,' and criminals.”

How we understand race and ethnic identity affects how we understand social and economic inequality, says Kohler-Hausmann. “One of the vehicles for undermining social programs was fusing them with racist characterization of African Americans, who were actually often the minority of the people benefiting from these programs. Today, even as we see a movement to reform mass incarceration, there are still punitive laws being passed about welfare.”

Increasingly punitive social and criminal policy has had broad effects on our democracy. Research by Jamila Michener, assistant professor of government, shows how government policies have an effect on political engagement and depress voices in the greater polity. Recipients of social welfare programs also forgo rights; those receiving AFDC assistance can be drug tested , have their houses searched, or limitations placed on where they can spend money. Kohler-Hausmann explains that “Policies that degrade the civic standing of the poor make it harder for them to be heard in public dialogues over inequality.”

Anna Haskins, assistant professor of sociology, has shown that having a father who is incarcerated perpetuates inequality across generations by affecting how ready children are for school, emotionally and behaviorally. She finds that boys, in particular, who have imprisoned fathers are already behind when they arrive in kindergarten at age five, and are more likely to be placed in special education, held back a grade, or continue to experience socio-emotional problems by age nine.

Systemic Surveillance

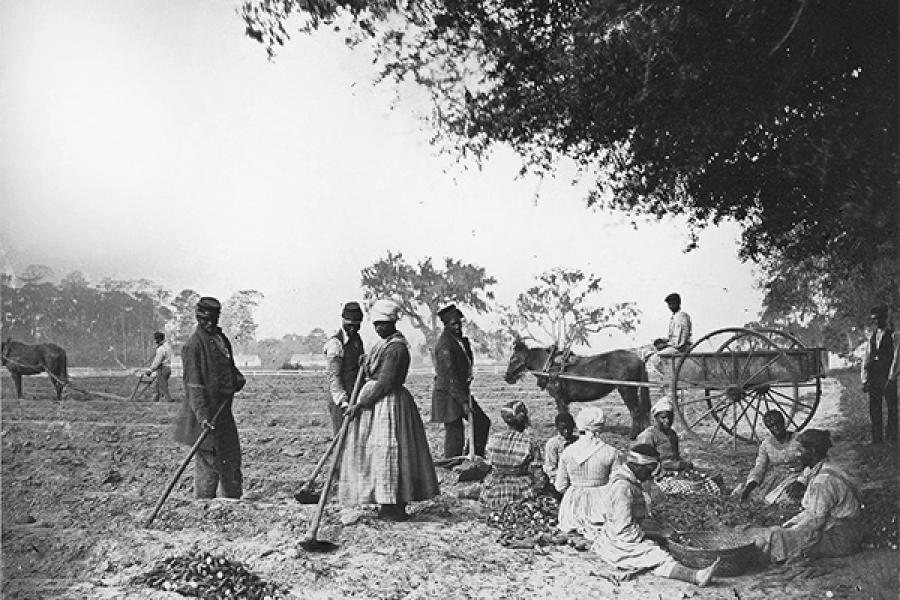

Professor of History Edward Baptist sees a connection between the research he’s conducting on runaway American slaves and current issues with the criminal justice system. Did the efforts to catch runaway slaves influence attitudes and law enforcement in the U.S relating to blacks?

“Black people’s movements through and into spaces is something that is constantly noted in the 19th century as acceptable or not acceptable,” he explains. “They’re understood as a problem, especially someone whose name wasn’t known or who wasn’t acting in an expected way. That’s still an issue for us in our country today. Blacks constantly encounter the attitude of ‘you don’t belong here,’ such as when they’re followed in a store or stopped by police. Do black people belong in these spaces, or are they in effect fugitives? And how much of this is created by policy and how much by culture?”

Baptist’s latest project looks at the way surveillance – controlling space and activities – is a systemic part of our culture that has been carried forward from the institution of slavery. “The white population was actively involved in maintaining the slavery regime by policing Black movements through space, seeing them as suspicious, a problem that had to be investigated,” Baptist explains. “Black people’s movements through and into spaces were something that 19th-century white America constantly monitored, and saw as either acceptable or not acceptable. African Americans were surveilled, and constantly seen as potential threats--especially those whose names weren’t known, or who didn’t seem to be working like slaves to add to white wealth. Some very similar patterns seem to persist in our our country today. On a large scale it’s easy to see that. For example, police are much less likely to find contraband in a Black driver’s car, yet they far more frequently stop Black travelers’ cars--because they ‘look suspicious.’ How much is this policy, and how much is this culture – are Black people seen as belonging in these spaces, or are they effectively still seen as fugitives?”

Another example, says Baptist, is racialized law enforcement that makes a huge investment in policing areas perceived as “drug corners.” “This is very expensive policy, yet one publicized by the news media as if it is the essence of policing. But the policy is more about controlling black activity in space than it is about preventing crimes against black lives. In contrast, the investment in homicide detectives where most of the murders taking place in areas like South Los Angeles is very low.”

Capitalism and Inequality

The lower 40% of income earners in this country carry significant debt; if they own a home, it is often heavily mortgaged. Such debt creates intense pressure to find and keep a job. But being out of work is a frequent experience for people in a capitalist economy. The result is an inequity: the pressure to be hired doesn’t correspond to the pressure to hire. This raises a moral question, says Miller: should people who benefit from advantages in bargaining power be required to redistribute their wealth? Is it exploitation of workers, when the power of the exchange is all on one side?

One contribution of historic humanities is to stretch people’s viewpoints by showing how assumptions change over time, says Miller. One example is that of wage labor as an evil: Abraham Lincoln regarded wage labor as something to liberate yourself from: every man should have the means to be his own boss, with no one above him. “Some at the time even viewed workers as worse off than slaves, because if times were bad slaves were still fed and housed, whereas workers just got fired,” adds Miller.

“In my Black Radical Tradition class, I teach about that political tradition of thinkers and activists who always said that you cannot have racial justice without wholesale economic redistribution,” says Russell Rickford, assistant professor of history. “You don’t just racialize a group because you don’t like them. You racialize a group in order to expropriate their land, their resources, their wealth. That’s how the incredible opulence and wealth of this society was generated, with 500 years of uncompensated or super-exploited labor. Modern capitalism is an inherently racialized project. You cannot have any kind of racial reconciliation or racial justice without wholesale redistribution. South Africa had the end of apartheid and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, but there was no redistribution, so it has the same kind of economic structure as before, with the same structural inequalities.”

Notes Weeden, “there are all sorts of institutions in any country or labor market that protects some types of workers or in some cases protect owners of capital. In the last 20 years, there have been numerous institutional changes that have protected workers at the top of the income distribution while eliminating protections to those on the bottom.”

Weeden’s research looks at the institutional sources of income inequality, as well as the gender gap in earnings, such as how the increase in hourly wages for long work hours has affected the motherhood wage penalty and the fatherhood wage premium.

One example Weeden points to are various bottlenecks in the educational system, some stemming from inadequate primary schools, which prevent the supply of college-educated workers from keeping up with demand. “Those who do get a college degree benefit, indirectly, because their wages are actually higher than what they would be if there were no bottlenecks in the educational system,” explains Weeden.

“The contradiction is that what accompanies capitalist expansion is often deepening inequality and declining freedom. For example, the expansion of the cotton economy resulted in a deepening of slavery and a stripping away of freedoms,” says Baptist, who is part of the History of Capitalism Initiative and author of “The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism” (Basic Books, 2014).

“When enslaved African Americans ran away they were trying to rewrite the story of capitalism and their relationship with this expanding capitalist system. They were making a decision that their relationship to capitalism was not going to be that of property, but that of a wage worker. This was the most effective resistance in the history of resistance to the deepening inequality in the U.S.,” says Baptist, because of the driving influence of those who escaped slavery on the abolitionist movement and the coming of the Civil War.

Residential Segregation

“Policymakers across the political spectrum seem to believe that, aside from random acts of racial discrimination, we more or less live in a world where residential segregation is a reflection of individual choice,” says Noliwe Rooks, associate professor of Africana studies, adding that “the racial divide is either not considered to be very bad, or is now taken for granted.”

But in fact this this attitude is wrong, says Rooks: studies show that metro areas with the highest levels of segregation have the largest health inequities, resulting in shorter life spans for black and Latino residents of these areas. And research has shown that two-thirds of the difference between test scores and grades for black and Latino students in the top 30 U.S. schools could be predicted based on the racial segregation of the students’ home neighborhoods.

“We know from 30 years of research that test scores and college-level success are far lower for students of color who attend racially segregated schools,” Rooks says. “And of course we know that schools today remain segregated because neighborhoods remain segregated.”

Rooks’ new seminar, Race and Social Entrepreneurship: Food Justice and Urban Reform, examines the issue of food justice in Ithaca and surrounding areas, which is often related to residential segregation, and explores innovative approaches for bringing about social equity and justice in relation to food availability, access and sustainability for those on a fixed or low income. The course is both a University Course, and part of an Engaged Cornell Curriculum Grant awarded to Africana Studies. Students in the service learning course will work in collaboration with senior citizens who live at a local residential facility, McGraw House, and are on a fixed income in order to explore both barriers and workable solutions to food access, availability and affordability. In addition, students in the course will work with with local farmers, non-profits and community activists in order to learn about area organizations and experiments intervening in the issues of food justice.

“Our goal is understand how sustainable development can be achieved in the context of racism and social inequality, with a focus on contemporary and historical efforts to build lasting institutions or movements,” says Rooks.

Minoring in Inequality Studies

Cornell offers a minor in inequality studies, which is housed in CSI and the department of sociology. The minor gives students a firm grounding in the literature on inequality, through such large and popular courses as Social Inequality, which gives an overview of theoretical and empirical scholarship on inequality in the social sciences, and Controversies about Inequality, a University Course that focuses on contemporary social scientific and policy debates on inequality. The minor requires students to take courses from multiple social science disciplines as well as offers electives in the humanities, and it allows them to tailor their studies to focus on different aspects of inequality, such as a track on ethics and social justice.

The minor has been very successful and is growing in popularity as inequality has entered public discourse again, says Weeden. Since 2004, the minor has graduated more than 600 students, and 225 enrolled in AY 2015-16. About half of the minors are in Arts & Sciences.

“The Inequality Studies minor was the catalyst that fostered my passion towards social justice, for which I will always be grateful, says Allen Fung ’07. “After studying in-depth the various forms of inequality (racial, gender, socio-economic, etc.) present throughout American history, I knew that I wanted to be part of the effort in correcting these various inequalities.”

Winnie Tong ’14 echoes that sentiment: “as a woman of color from Brooklyn, I have gained so much through the Inequality Studies minor because it allowed me to learn more about the structural and systematic issues within our society. Although I might not have found all the solutions to the larger issues we discussed in class, the minor definitely played a significant part in steering me onto a path of social justice and working with communities of color.”

This feature is part of the New Century for the Humanities "Big Ideas" project to explore broad contemporary themes in the humanities. The New Century for the Humanities is a series of events and projects initiated to celebrate the opening of Klarman Hall, the first building dedicated to the humanities on Cornell's central campus in more than 100 years.